Here’s a charming little piece, originally written for the lute, that I’ve adapted for guitar.

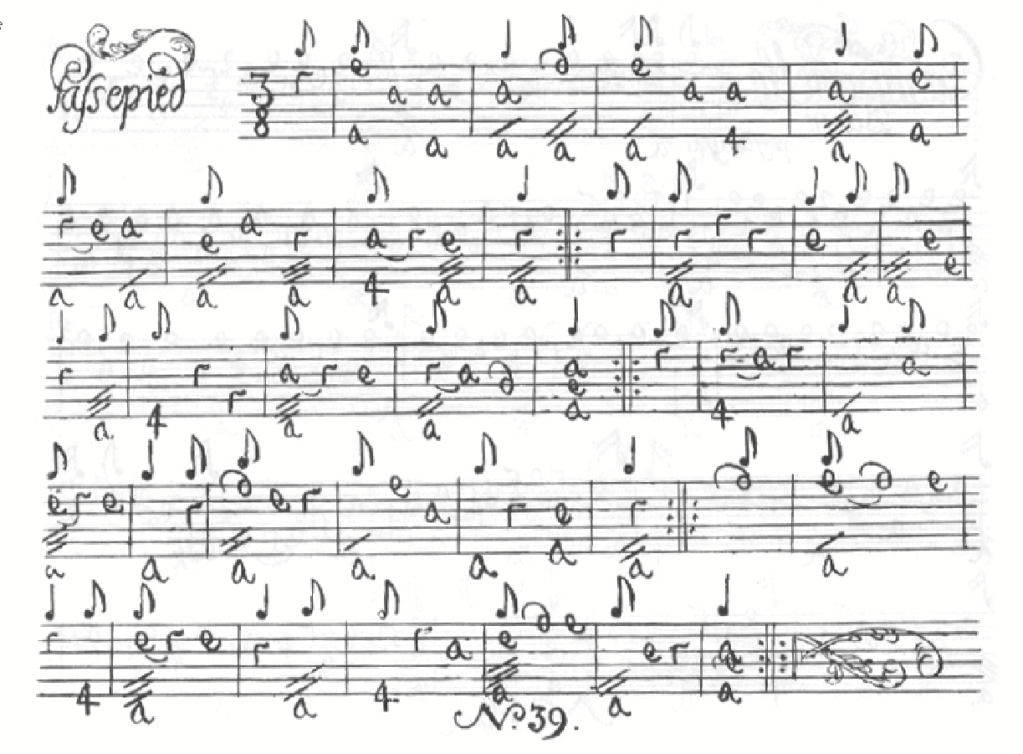

[Image from IMSLP, public domain.]

The source

This piece comes from a book published in 1747, entitled David Kellners XVI. Auserlesene Lauten-stücke, or Selected Lute Works. It was written by David Kellner, a German composer who lived most of his professional life in Sweden working as a church organist.

The title is a little funny, because there appear to be 17 separate compositions in there, even if we count the Sarabanda and Double on page 44 together as one. There’s an anonymous suggestion on IMSLP that the XVI is intended to mean that it’s Kellner’s sixteenth work, which is possible but hard to verify based on what’s known of his written output. His life story isn’t germane to this piece, but you can read more about him here if you’re curious.

There don’t seem to be any other records from Kellner’s lifetime that refer to him playing the lute. So, either this was a talent of his that wasn’t as much in the public eye as his organ playing, or it could be that he wrote the material on keyboard and fingered it for the lute for publication. Though that seems unlikely to have been a winning sales idea, as 1747 is at the tail end of the lute’s era of prominence.

The book contains mostly short pieces in traditional dance forms, with a few loose fantasias, and one really long Chaconne. I’m enjoying getting to know them. I hope to share more of them over time, because the guitar could use more characteristically Baroque repertoire, from a wider variety of composers, that isn’t as intense and hard to play as some of the usual suspects.

The form

The Passepied by Kellner’s time was a courtly dance in a sprightly triple meter — in this case, 3/8 — similar to a minuet.

This one’s got four 8-bar sections, each of which is intended to repeat. It stays in its home key of A major the whole way, never fully modulating to any other key. But the first and third sections end on E (the dominant chord — this is called a “half cadence” because it leaves a feeling of being unfinished), while the second and fourth sections end back on the A to give a more final feeling. So you can look at the sections as being paired up into two larger-scale blocks.

Adapting from lute to guitar

This Passepied has two distinct voices: a melody and a bass. The main difference in adapting it to the guitar is that the bass voice is almost exclusively played in the diapasons — the lowest strings of the lute, which are often played open (some of them don’t have frets at all and can only be played open). This poses some interesting issues.

First, the bass goes down to a C#, which is lower than the guitar can reach. We have a few options to deal with this:

- Change the key so that the voices will fit in the guitar’s register. I have a slight preference for keeping original keys when it’s convenient to do so, and A major is an extremely convenient key for the guitar: it has the tonic, subdominant, and dominant notes (scale degrees 1, 4, and 5, or A, D, E respectively) all as open strings in the bass register.

- Tune at least the low E string of the guitar down. Retuning can get access to some additional bass notes, and it can also make some fingerings easier. But it can make others harder. (In transcribing some earlier lute music for guitar, it’s very common to retune the guitar’s G string to match the way those lutes were tuned. By Kellner’s period though, lutes had evolved to use a D minor tuning that is farther from the guitar’s standard tuning.) In practice I find as a player that retuning is a pain to have to do when it’s not absolutely necessary, especially for a short little piece like this.

- Raise the bass notes by an octave. In this piece, there’s a relatively wide spacing between the bass and the melody, so apart from the first couple of measures there’s room to move the bass voice up without clashing.

- Some combination of the above.

I chose to stay in A major and work within the guitar’s standard tuning. I also tried to maintain the shape of the bass part when possible. For example, in the first section, you could play several of the notes in the second phrase in their original lower octave, and only jump up for the impossible notes below the low E. But I felt that it sounded better to move the whole phrase up, because it keeps the internal motion intact. Closing the interval between the bass and the melody does change the overall feel a little, making the texture more dense and less spacious, but on the other hand it also emphasizes the parallel motion of the two voices. There’s always a balance to be struck between these considerations; in later sections that ideal of keeping the shape of the bass part is outweighed by the convenience of having the open string notes available, or of making other fingering decisions easier.

Another interesting thing about the lute’s diapason strings is that they often are left to ring out on top of each other (though the performer can choose to mute them with the right hand). This can cause some nice moments of dissonance, like in the descending stepwise motion in the second section. With the guitar, this effect is both harder to achieve (because we have fewer strings we can leave ringing and fewer open notes) and more prominent when it does happen (because of the strong resonance and long sustain the guitar has in that register compared to the lute, which typically has relatively more attack and less sustain). And on guitar, when bass notes are held for too long, they can muddy the harmony. So there’s a fine line in bringing out those characteristic lute moments without overdoing it. Again, this is partly in the control of the player, but the arrangement should keep this in mind. For example, in the second section, in the E-to-D and D-to-C# motions in the bass, the player can choose to leave the first note ringing when the second is played or not.

I also think it’s worth looking at the original fingering for the melody part, and thinking about what aspects to carry over. For example, in a few places the original score uses slurs to indicate where the player should play a hammer-on with the left hand instead of plucking the string with the right hand. I chose to maintain these articulations even when they’re less convenient on the guitar, like at the start of the third section, because I think they contribute to the feel.

There’s one notable place in measure 7 where the original tablature doesn’t have a hammer-on but I’ve been forced to insert one. The original tab says to play a C# on one string followed by a D on the open string immediately above, which introduces a really tasty little passing dissonant crunch that the player can choose to emphasize or minimize depending on how much or how little overlap they allow between those notes. However, it’s not really possible to finger that on guitar while also playing the E in the bass voice, unless I drop the E down to the lower octave (thus breaking the contour of the bass part). So we lose that opportunity. On the bright side, the added hammer-on mirrors the hammer-on that happened at the same spot in the previous bar, which lends a bit of extra consistency between those measures within that descending passage.

All of this detail is to illustrate that there are a lot of nuanced decisions and considerations in transcribing even a simple piece like this one, and a lot of goals that can sometimes conflict. In another post I’ll try to articulate some of those high-level goals.

Download

You can download my arrangement here:

It contains both notes and tablature in standard guitar tuning.

If you try it out, I’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback!

Leave a reply to Phantasia in A Minor — David Kellner – Guitar Pieces Cancel reply